🐙 Search engine for emoji in go

| Published | |

| Reading time | 13 minutes |

| Licence |  |

| Tags | Tech - Go - Emoji - Proofread by an LLM |

For a project of mine, I had to handle emojis. The goal was to create a search engine to find emojis. I am not starting from scratch and have to include my code into an already existing Go program. So, let’s see how to build a little search engine for emojis in Go.

TL;DR: The full result is available here: git2.riper.fr/ztec/emoji-search-engine-go

You can also test and see the final result. All details here: poulpe.ztec.fr - The emoji search engine open-sourced

🐗 Emoji! Get them all!

First, I had to find the list of all available emojis. Easy! You can find it on the official Unicode website.

https://unicode.org/Public/emoji/15.0/emoji-test.txt

This file look like this

[…]

# group: Smileys & Emotion

# subgroup: face-smiling

1F600 ; fully-qualified # 😀 E1.0 grinning face

1F603 ; fully-qualified # 😃 E0.6 grinning face with big eyes

1F604 ; fully-qualified # 😄 E0.6 grinning face with smiling eyes

1F601 ; fully-qualified # 😁 E0.6 beaming face with smiling eyes

1F606 ; fully-qualified # 😆 E0.6 grinning squinting face

1F605 ; fully-qualified # 😅 E0.6 grinning face with sweat

[…]

Basically, there is the Unicode code, the character itself, and a description. The file is dedicated for machines, so it should not be hard to load and parse it.

Before starting head down, let’s do our due diligence and check what the community has already done.

I found:

- github.com/enescakir/emoji, last updated in 2020.

- AkinAD/emoji, last updated in 2022 (a fork of the first).

- github.com/kenshaw/emoji, last updated in 2021.

Looking at the code of those libraries, I found something fascinating: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/github/gemoji/master/db/emoji.json

This file, which is regularly updated, is perfect and can be parsed with less effort. Moreover, it already contains some metadata like aliases.

This is the way, lets load this file

1package pouet

2

3import (

4 "encoding/json"

5 "github.com/go-zoox/fetch"

6)

7

8type EmojiDescription struct {

9 Emoji string `json:"emoji"`

10 Description string `json:"description"`

11 Category string `json:"category"`

12 Aliases []string `json:"aliases"`

13 Tags []string `json:"tags"`

14 HasSkinTones bool `json:"skin_tones,omitempty"`

15 UnicodeVersion string `json:"unicode_version"`

16}

17

18type GithubDescriptionResponse []EmojiDescription

19

20func fetchEmojiFromGithub() (results []EmojiDescription, err error) {

21 response, err := fetch.Get("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/github/gemoji/master/db/emoji.json")

22 if err != nil {

23 return

24 }

25 err = json.Unmarshal(response.Body, &results)

26 return

27}

I used github.com/go-zoox/fetch to fetch the file just because I’m a lounger

🦓 Emoji, Scan them all!

In my program, I already use Bleve to index and search through other things, so I will do the same here. The operation is pretty simple as I do not have to store anything and can keep an in-memory index.

1package pouet

2

3import (

4 "fmt"

5 "github.com/blevesearch/bleve/v2"

6 "github.com/sirupsen/logrus"

7 "strconv"

8 "strings"

9)

10

11var (

12 index bleve.Index

13 emojis []EmojiDescription

14)

15

16func indexEmojis() error {

17 // we create a new indexMapping. I used the default one that will index all fields of my EmojiDescription

18 mapping := bleve.NewIndexMapping()

19 // we create the index instance

20 bleveIndex, err := bleve.NewMemOnly(mapping)

21 if err != nil {

22 return err

23 }

24 // we fetch the emoji from the internet. This can fail, and may be embedded for better performance

25 e, err := fetchEmojiFromGithub()

26 if err != nil {

27 logrus.WithError(err).Error("Could fetch emoji list")

28 return err

29 }

30 emojis = e

31 for eNumber, eDescription := range emojis {

32 // this will index each item one by one. No need to be quick here for me, I can wait few ms for the program to start

33 err = bleveIndex.Index(fmt.Sprintf("%d", eNumber), eDescription)

34 if err != nil {

35 logrus.WithError(err).Error("Could not index an emoji")

36 }

37 }

38 index = bleveIndex // we make the index available

39}

Once indexEmojis is called, I have an index ready to be used to search for emojis. Let’s test it.

1package pouet

2

3import (

4 "fmt"

5 "github.com/AkinAD/emoji"

6 "github.com/blevesearch/bleve/v2"

7 "github.com/sirupsen/logrus"

8 "strconv"

9 "strings"

10)

11

12var (

13 index bleve.Index

14 emojis []EmojiDescription

15)

16

17func Search(q string) (results []EmojiDescription) {

18 if index == nil {

19 // no Index mean indexEmojies was not called yet or did not finished. No results (boot process)

20 return

21 }

22 // we create a query as bleve expect.

23 query := bleve.NewQueryStringQuery(q)

24 // we define the search options and limit to 200 results. This should be enough.

25 searchrequest := bleve.NewSearchRequestOptions(query, 200, 0, false)

26 // we do the search itself. This is the longest. Approximately few hundreds of us

27 searchresults, err := index.Search(searchrequest)

28 if err != nil {

29 logrus.WithError(err).Error("Could not search for an emoji")

30 return

31 }

32

33 // we return the results. I use the index to find my original object stored in `emojis` because it's simpler. Optimisation possible.

34 for _, result := range searchresults.Hits {

35 numIndex, _ := strconv.ParseInt(result.ID, 10, 64)

36 results = append(results, emojis[numIndex])

37 }

38 return

39}

I decided to use the NewQueryStringQuery as it allows for many options of searching directly from the query string.

I will be able to search within fields or add modifiers. I use it a lot for my other purposes; it might be less useful here, but it does not cost a lot, so I kept it.

Open your mind and imagine a clip-show of me adding the above code in my program and creating the interface to send the query and display the results.

🧋 Fuzzy search

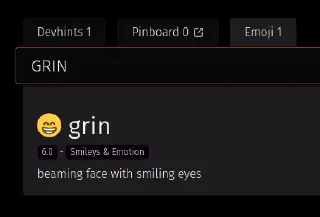

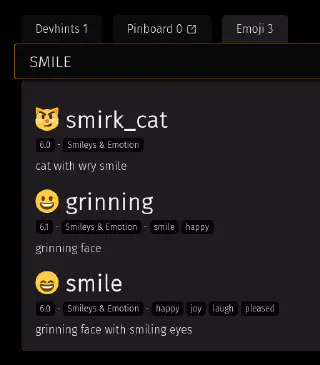

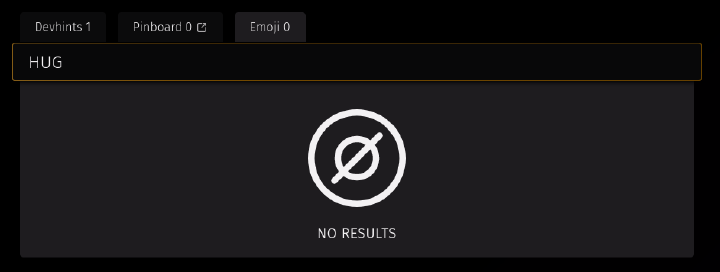

Cool, the results seem promising. But there seems to be a problem.

I should have an emoji here, 🤗 to be exact. If I add the s to the query, it finds it, but not without it. Let’s try

to enhance the search for this kind of purpose by adding a bit of fuzziness to the search.

The idea is to allow some inexact words to match the query. For that, we will use what’s called Levenshtein distance.

In fact, as I already said, I’m a slacker, so Bleve will do it for me. Unfortunately, I could not find any way

to add a default fuzzy parameter to query search. I still can add ~ to words of my search to enable fuzzy search on them.

As my expectations are not high, I will do it the “just hack it” way. If I have no results from the query, I will do a specific

fuzzy search instead.

1func Search(q string) (results []EmojiDescription) {

2 if index == nil {

3 // no Index mean indexEmojies was not called yet or did not finished. No results (boot process)

4 return

5 }

6 // we create a query as bleve expect.

7 query := bleve.NewQueryStringQuery(q)

8 // we define the search options and limit to 200 results. This should be enough.

9 searchrequest := bleve.NewSearchRequestOptions(query, 200, 0, false)

10 // we do the search itself. This is the longest. Approximately few hundreds of us

11 searchresults, err := index.Search(searchrequest)

12 if err != nil {

13 logrus.WithError(err).Error("Could not search for an emoji")

14 return

15 }

16

17 // If we have no results we try to do a basic fuzzy search

18 if len(searchresults.Hits) == 0 {

19 // this time, we create a fuzzy query. The rest is the same as before. CopyPasta style.

20 fuzzyQuery := bleve.NewFuzzyQuery(q)

21 searchrequest := bleve.NewSearchRequestOptions(fuzzyQuery, 200, 0, false)

22 searchresults, err = index.Search(searchrequest)

23 if err != nil {

24 logrus.WithError(err).Error("Could not search for emoji")

25 return

26 }

27 }

28 // we return the results. I use the index to find my original object stored in `emojis` because it's simpler. Optimisation possible.

29 for _, result := range searchresults.Hits {

30 numIndex, _ := strconv.ParseInt(result.ID, 10, 64)

31 results = append(results, emojis[numIndex])

32 }

33 return

34}

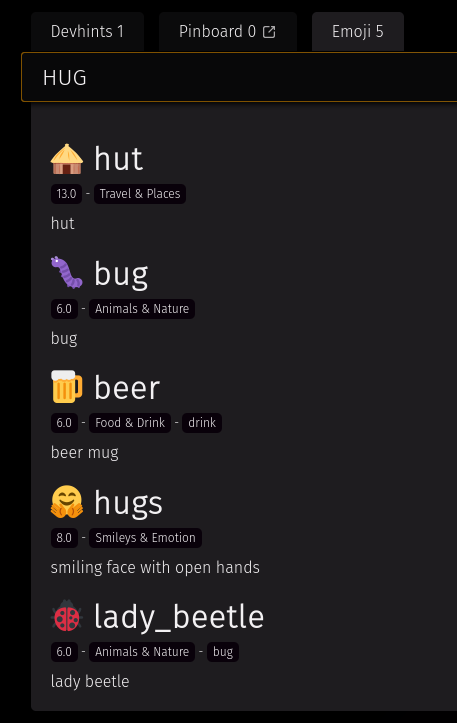

This time, I have my hugs emoji when I search for hug. I also have other results, but that’s fine for me. I don’t expect

to have only one result and picking the right one as long as it is visible on screen with few to no scrolls is ok for me.

side note: I could have also used prefix search, but I don’t always search using the beginning of an emoji’s name, so I prefer using the fuzzy search.

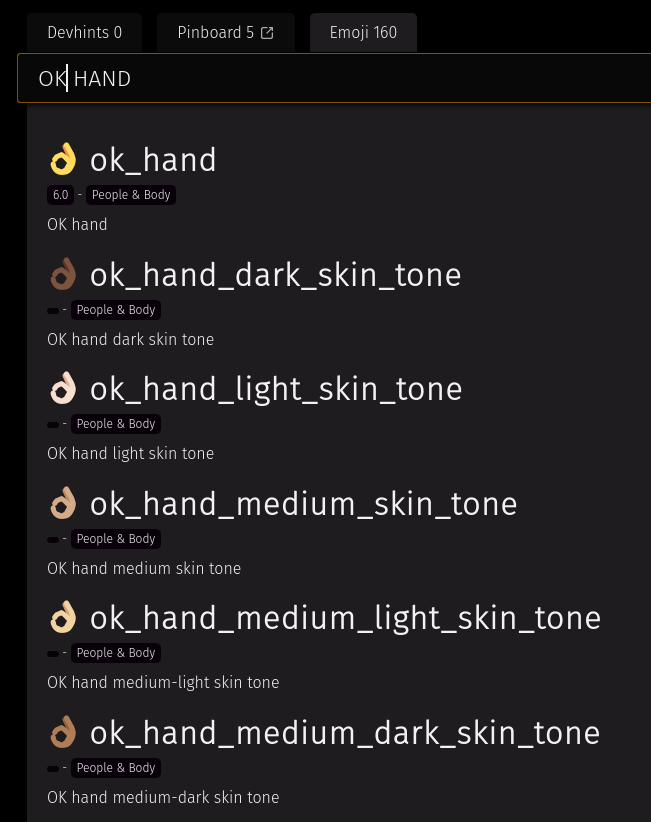

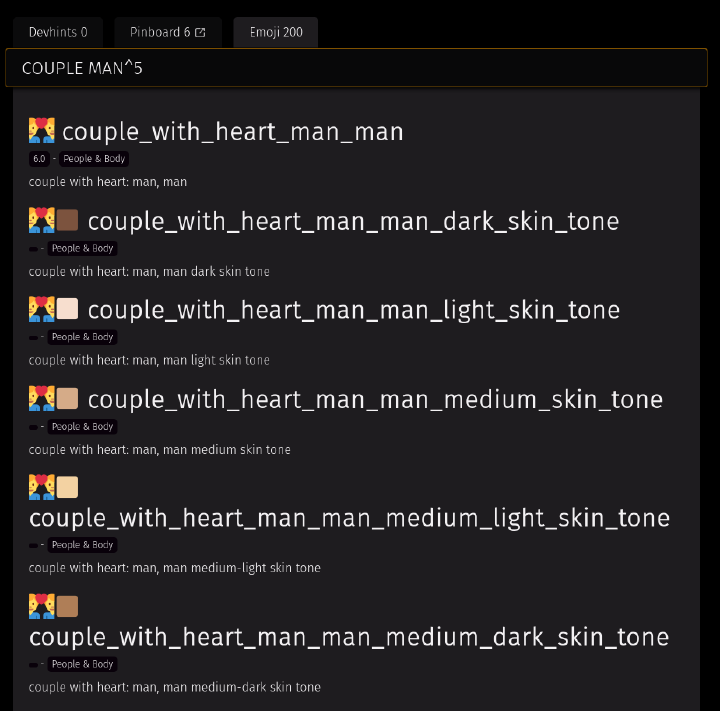

🟪 Skin tones

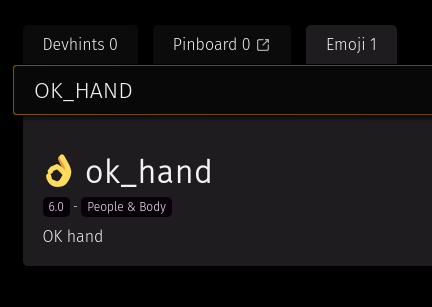

If I search for ok hand I find the emoji, right? But as you can see, there is only the standard variation - the yellow one.

I would like to have the skin tone variation as well.

Open your mind again and imagine a narrator with a deep voice popping in your head and saying the following: “Zed did not know how hard it would be to include those fancy skin toned emojis. Hours would pass before he finally understands.”

Before continuing, I need to explain (what I understood) how emojis and UTF-8 works for skin tone variations. UTF-8 characters can be composed together. This allows to create what we call ligatures. Basically, you take the code of two characters, and you smash them together into one UTF-8 character. On your screen, if your reader and font are compatible, you will see a different character in place of the two characters. The beauty of it is that even if your reader or font are not compatible, you will still see the original characters anyway. Cool, right?

Emoji skin tone is handled like this. You “smash” together the original emoji and the skin tone color to create a new emoji of the original one, but the yellow is replaced by the skin tone.

1F44C ; fully-qualified # 👌 E0.6 OK hand

1F44C 1F3FB ; fully-qualified # 👌🏻 E1.0 OK hand: light skin tone

1F44C 1F3FC ; fully-qualified # 👌🏼 E1.0 OK hand: medium-light skin tone

1F44C 1F3FD ; fully-qualified # 👌🏽 E1.0 OK hand: medium skin tone

1F44C 1F3FE ; fully-qualified # 👌🏾 E1.0 OK hand: medium-dark skin tone

1F44C 1F3FF ; fully-qualified # 👌🏿 E1.0 OK hand: dark skin tone

The first column contains the UTF-8 code for each emoji. As you can read, the first one is the same and is the ok_hand emoji

itself. The second code is for the skin tone, so we have a list of each available skin tone.

1 tones := map[string][]rune{

2 "light skin tone" : []rune("\U0001F3FB"),

3 "medium-light skin tone" : []rune("\U0001F3FC"),

4 "medium skin tone" : []rune("\U0001F3FD"),

5 "medium-dark skin tone" : []rune("\U0001F3FE"),

6 "dark skin tone" : []rune("\U0001F3FF"),

7 }

The original library, and most libraries I’ve seen, handle emojis as strings and manipulate them with string methods using the \Uxxxxxxxx format.

Golang has a type dedicated to UTF-8 character management: the rune. I decided to use it. Unfortunately, there are not many examples online of rune usage, especially with ligatures.

I used the string representation to easily make the connection between the UTF-8 code and the runes in Go.

Now, we need to create a new emoji for each skin tone. Not all emojis can support skin tone. I could parse the original Unicode file, but if you paid attention, the JSON file I fetched already has this information.

1func enhanceEmojiListWithVariations(list []EmojiDescription) []EmojiDescription {

2 tones := map[string][]rune{

3 "light skin tone" : []rune("\U0001F3FB"),

4 "medium-light skin tone" : []rune("\U0001F3FC"),

5 "medium skin tone" : []rune("\U0001F3FD"),

6 "medium-dark skin tone" : []rune("\U0001F3FE"),

7 "dark skin tone" : []rune("\U0001F3FF"),

8 }

9 for _, originalEmoji := range list {

10 // we only add variations for emoji that supports it

11 if originalEmoji.HasSkinTones {

12 // we do it for every skin tone

13 for skinToneName, tone := range tones {

14 // we make a copy of the emojiDescription

15 currentEmojiWithSkinTone := originalEmoji

16

17 // This is the important bit that took me hours to figure out

18 // we convert the emoji in rune (string -> []rune). An emoji can already be composed of multiple sub UTF8 characters, therefore multiple runes.

19 // we append to the list of runes the one for the skin tone.

20 // finally, we convert that in string using the type conversion. Using fmt would result in printing all runes independently

21 currentEmojiWithSkinTone.Emoji = string(append([]rune(currentEmojiWithSkinTone.Emoji), tone...))

22

23 // we adapt the description and metadata to match the skin tone

24 currentEmojiWithSkinTone.Description = fmt.Sprintf("%s %s", currentEmojiWithSkinTone.Description, skinToneName)

25 aliases := []string{}

26 for _, alias := range currentEmojiWithSkinTone.Aliases {

27 // we update all aliases to include the skin tone

28 aliases = append(aliases, fmt.Sprintf("%s_%s",alias,strings.ReplaceAll(strings.ReplaceAll(skinToneName,"-", "_")," ", "_")))

29 }

30 currentEmojiWithSkinTone.Aliases = aliases

31 // I cleared the unicode version because some emoji with skin tone were added way after their original. I could parse the unicode list,

32 // but I'm a loafer, so I did not.

33 currentEmojiWithSkinTone.UnicodeVersion = ""

34 // we add the new emoji to the list

35 list = append(list, currentEmojiWithSkinTone)

36 }

37 }

38 }

39 return list

40}

The key 🔑 here is this line:

1currentEmojiWithSkinTone.Emoji = string(append([]rune(currentEmojiWithSkinTone.Emoji), tone...))

I’m no expert in Go, and I probably missed something, but after hours of playing with fmt to print the emoji with ligatures

and failing, always two characters were displayed. I inadvertently used type conversion, and it worked. I have no idea why it took me two 🖕🏿 hours to do it.

We now have our skin tone variations! 🎉

🚫 Unsupported Emoji

My computer and my phone do not support Emoji version 14 and higher well. But, as I said earlier, the beauty of UTF8 ligatures is that even if you cannot process them fully, you get the characters. This way, you can still understand the intention.

If you want to test it yourself and tinker with it, you can find the full working example in this repository git2.riper.fr/ztec/emoji-search-engine-go.

You can also test and see the final result. All details here: poulpe.ztec.fr

⁉️ Why did I do all of that ?

First of all, why not. Just playing with emoji is fun, sort of. But mostly, my goal was to have on hand an emoji finder to easily copy them elsewhere. Every system I found online had flaws that were annoying.

- way too slow to load or search

- way too useless. I don’t want to search for my emoji in a huge list of yellow icons

The best solution I had was a shortcut to the unicode list itself. Not all common names are present, so I had to learn some official names. The big reason I decided to build my own search “engine” on that is “unicode website was down!” ⬇️

Yeah, I might be the only one in the world that knows that the unicode website sometimes does not respond, and be impacted by that! 🤣

⏭️ What’s next ?

This engine is really simple and basic. There are already ways to improve it. I have already included a reverse search, even if I did not talk about it here. The indexing engine is somewhat powerful and cool, but still misses some obvious cases. I’ll see what’s bothering me the most upon usage and improve it. Maybe the result will be open-sourced, but for that, I have a lot to do. Emojis are not the only things I have in my little search engine. 😉

Thank you reading this,

Bisoux 😗

| Title | 🐙 Search engine for emoji in go | ||

| Description | For a project of mine, I had to handle emojis. The goal was to create a search engine to find emojis. I am not starting from scratch and have to include my code into an already existing Go program. So, let’s see how to build a little search engine for emojis in Go. | ||

| Published | |||

| Updated | |||

| Type | |||

| Reading time | 13 minutes | ||

| Words | 2576 | ||

| Translation | English | https://blog.ztec.fr/en/2023/post/emoji-search-engine/ | |

| Français | https://blog.ztec.fr/2023/post/moteur-de-recherche-emojis/ | ||

| Tags | Tech - Go - Emoji - Proofread by an LLM | ||

| Licence | Except for quoted materials, which retain their original rights and attributions, this post and its content are published under the Creative Commons(CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) liscence  | ||

| OpenGraph | Image |  | |

| Title | 🐙 Search engine for emoji in go | ||

| Description | For a project of mine, I had to handle emojis. The goal was to create a search engine to find emojis. I am not starting from scratch and have to include my code into an already existing Go program. So, let’s see how to build a little search engine for emojis in Go. | ||

| Type | og:type = article twitter:card = summary_large_image | ||

| Promotions | https://mamot.fr/@ztec/110126905998815685 | ||

| https://twitter.com/Ztec6/status/1642354192411918336 | |||

Found a typo, or something bigger that probably killed a grammar nazy ? suggest a fix via github.

You can subscribe via